by Agosto

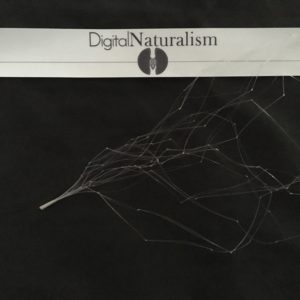

Agosto, arguable the most youthful member of the Dinacon crew, began his adventures on the island by drawing in the sand.

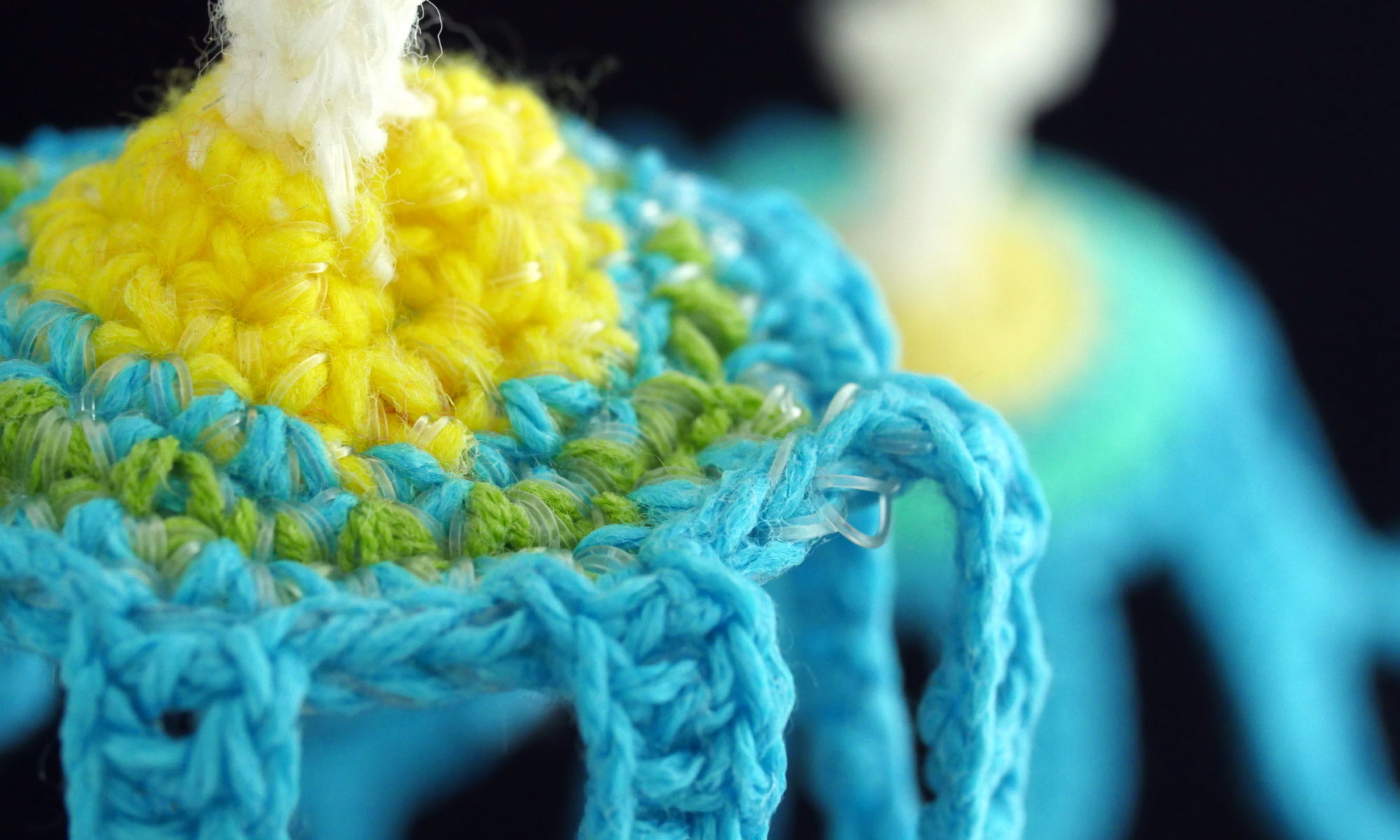

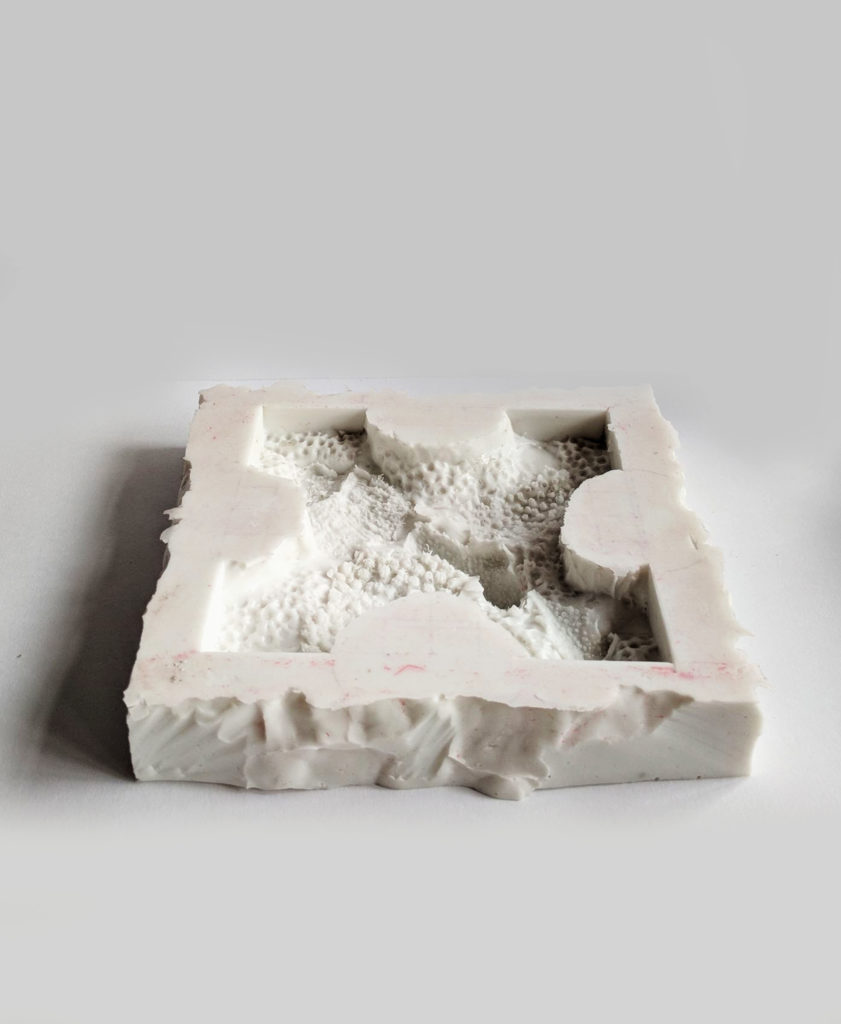

The island sand was much softer than the man made beach sand of his homeland, and he pondered these differences. He mused, what was home? He began to consider these questions while placing found coral in upright positions in the sand.

Upon seeing the variety of island creatures, such as hermit crabs and snails, he began to wonder how they viewed ‘home’, as they traveled with their shells on their backs. He sat for a moment, before drawing a large spiral in the sand and stared pensively at this simple view of a home.

He scavenged for his ‘homes’ nearby resources, and found fallen seed pods from trees, washed up pieces of old corals, and smooth sea pebbles.

He began placing the seed pods within the grooves of the spiral. In a nod to his homeland he began putting the coral pieces within the spiral spaces in a gaudi-esque style.

He finished the piece with it’s inhabitant snail, filled with pebbles.

Entitled Cargol, the temporary natural art piece, was meant to consider the transient meaning of ‘home.’

The piece remained beachside, changing colors as the pieces were weathered, wind blown and rained on.

Introduction

Introduction