“ There’s a real magic out here.

I heard that exact sentence, with that exact phrasing, at least three times during my stay at Dinacon. I heard the sentiment behind it countless times, and already knew what the next set of words would be, too.

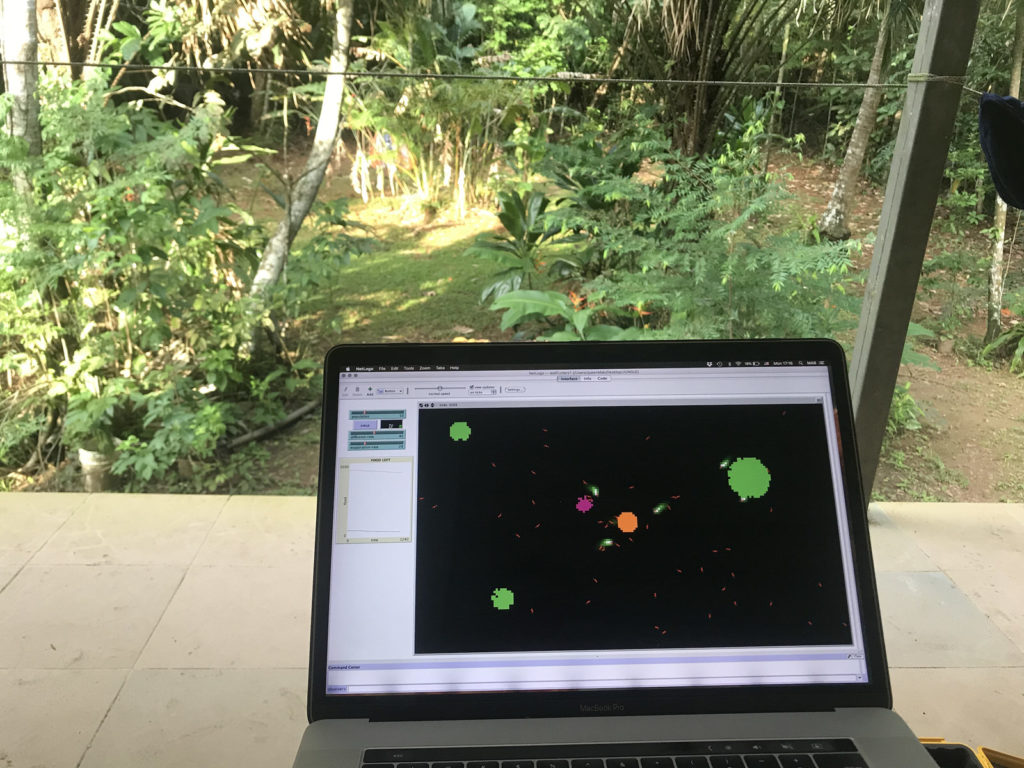

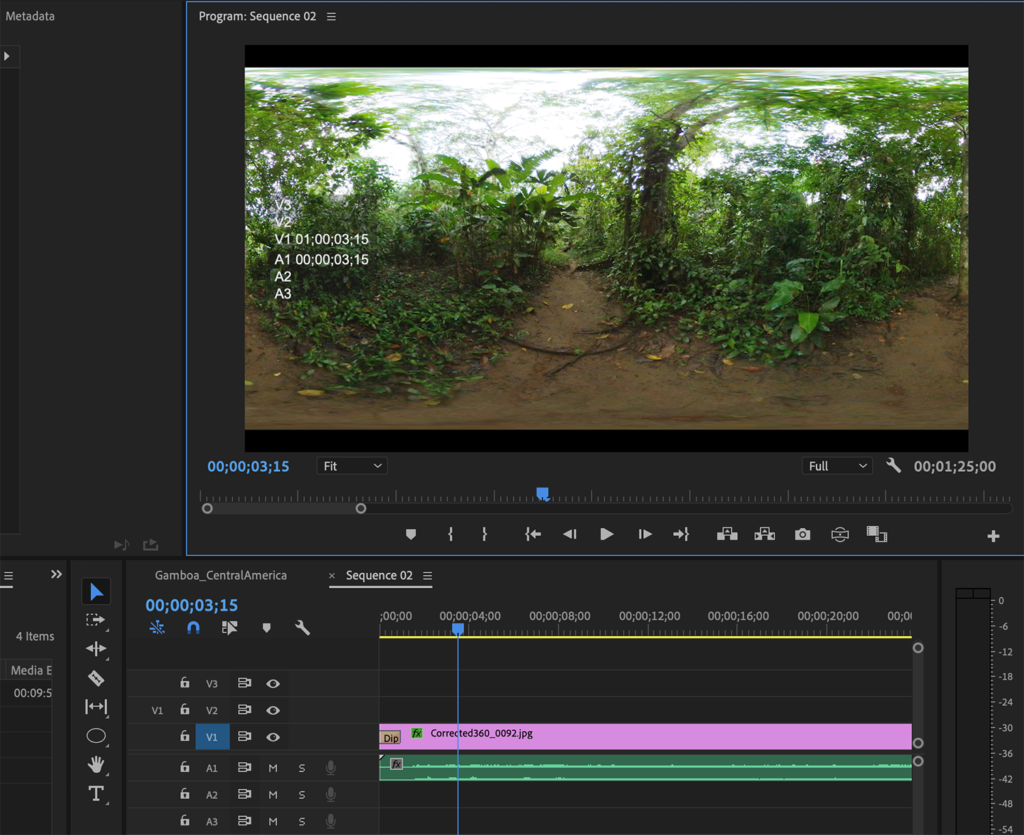

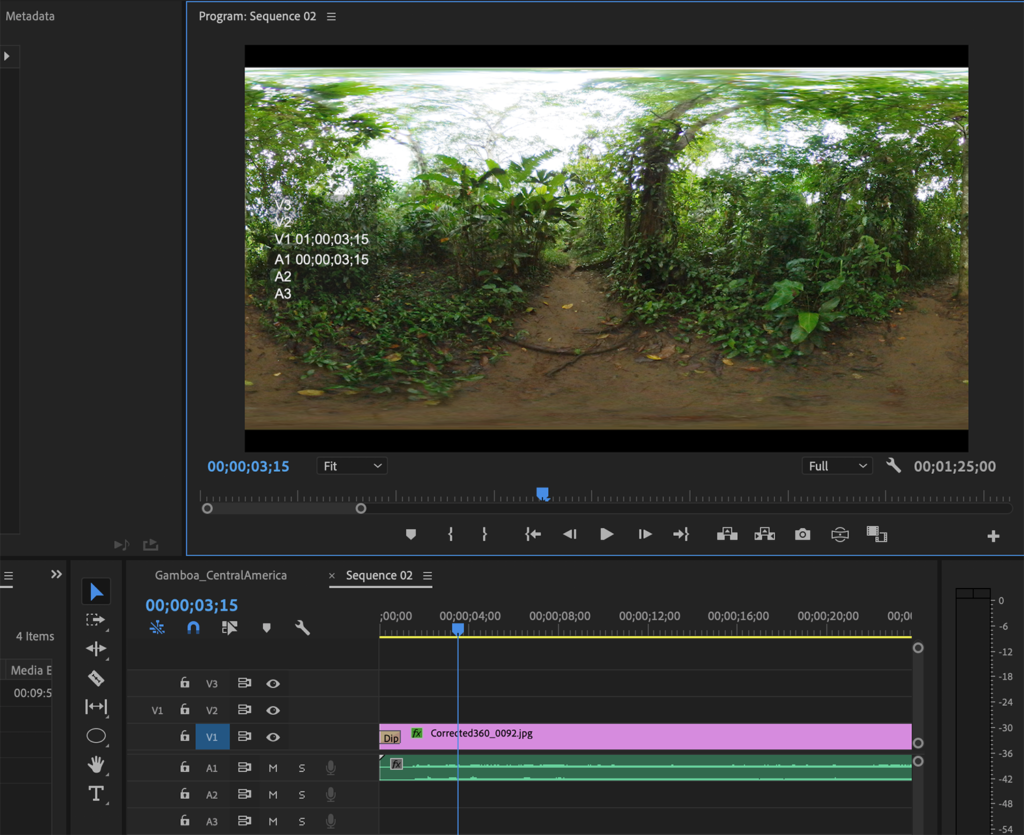

To start: I learnt how-to and made some Origami birds that can flap their wings, I learnt how-to solder and made two different DIY-Arduinos — and then used one to test variable water quality based on electrical current conductivity, I sketched the rainforest slightly abstractly (and definitely too faintly), I was part of a duo with Leoni Voegelin that called ourselves The Cutie Agoutis — and produced a few comedy ’shopped dystopic images for one of the Dinacon Open Houses, I worked along with definitely professional writer Nate Walsh on a computer generated poem, and I foraged for, helped design, and helped film a costume for a movie!

Every step of the way, the work I produced was preceded by my learning the skillset required to do it right before diving in. Part of the magic of Dinacon is just the sheer breadth of participant expertise and open expectation. The average participant probably had one or more graduate degrees, is an adjunct at a university, or is a lifelong experimenter and artist. And yet they were here. In the middle of the rainforest, in the middle of the rainy season. And it’s because they wanted to learn more from others at the conference. The tone of the conference was set early when one of the requirements was to receive commentary on your work from other people. The socializing aspect was built into the conference structure, and the inclusivity of attracting people from all walks of life, as long as they self-selected to be part of an experimental conference, ensured that everyone would be open to the interaction — which led to people furiously teaching each other everything they knew.

The largest (in scale) project I worked on was with Craig Durkin where we produced some cutting edge watermelon quality prediction research for one of the Dinacon Open Houses. We had gone shopping in Panama City during the morning, and on our way back wondered what, if anything, we could each display during the Open House. Craig, professionally a Materials Scientist, mused that we could just run a simple experiment to test whether or not it was a myth that people can predict watermelon quality prior to opening them up. I told him I can confirm it’s not a myth because I knew for a fact that I could do it. And we were off.

I think here hid another secret of the magic of Dinacon: the complete self-unimportance of the participants. Just reading through the Proceedings of the First Digital Naturalism Conference, everyone felt comfortable scaling back the scope of their project and talking about their work in exploratory, hilarious, matter-of-fact ways. The conference itself requires so little of the work that participants produce. A blog post, an infographic, and an art display of four sculptures with projected imagery all count as ‘something’ and are all celebrated as successes. The point isn’t to produce your best work, it’s to just produce. When the barrier for success is so low, people aren’t afraid to invest their time in one another’s projects, or to collaborate, because they see their own work as complete and valuable, and are ready to spread that joy with others.

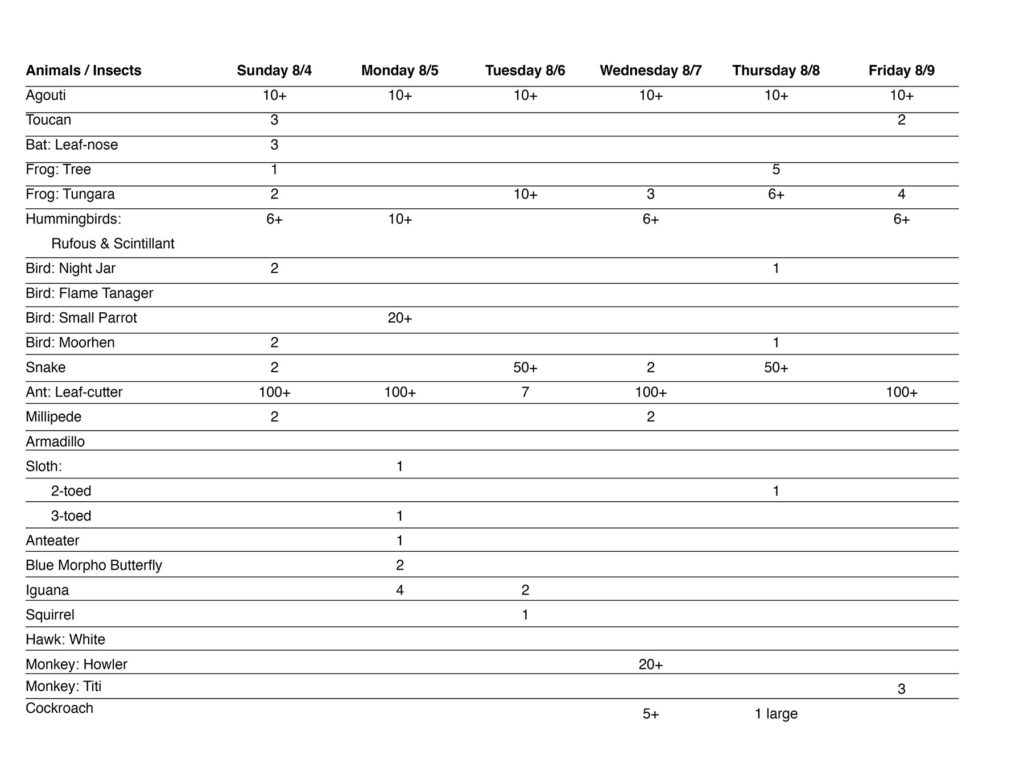

The other part of this is that with conference-wide projects, such as spotting a minimum of two sloths a day, everyone was encouraged to be out and about together daily, and with the conference-wide initiative to give talks in any shape or form everyone felt like part of the project-building process could be introducing people to their passions and part of the receiving-feedback process could be having input from experts external to their field. Everyone was on equal footing all the time, and the conference structure and culture maintained the momentum required for people to get to know and respect one another really easily.

“ There’s a real magic out here. For some reason it’s really, really easy to make friends out here.

I heard the words above, almost verbatim, multiple times. From people who hadn’t even met each other due to not having overlapping attendance days. If enough people agree magic exists in a place, if enough people’s hearts feel the same way independently, if enough people chant the same words across conversations after feeling as though they’re part of something larger than themselves, maybe I can be convinced that magic really exists.

I’m glad we have Dinacon in the world, and feel like I found my tribe. I hope it can be a vector for change in everyone who reads this.