1/3. Being hacked: ethnographic rigor within an anti-disciplinary community

As an anthropologist curious about how communities of technologists come together and create things, my mission entering Dinacon 2019–Panamá was clear: figure out what “digital naturalism” is. That is, what idea—other than a desire to hang out with agoutis—united a diverse array of technical and artistic professionals, compelling them to travel to the ghost town of Gamboa in the Canal Zone and then hike in the woods or solder electronics together?

I had read statements about digital naturalism by the ur-digital naturalist, Andrew Quitmeyer. I’d read through the Dinacon site and the documentation regarding Dinacon 2018–Thailand, and I’d spoken with a friend who is a longtime associate of Andy’s. But Andy’s technological and biological design principles—in part, that computers and other tools useful to biologists “have to leave the safety of the womb-like laboratories in which they were conceived and confront the messy challenges outside” (Quitmeyer 2017)—didn’t seem to completely map onto the documented projects from Dinacon 2018.

The call to bring a pragmatic maker, DIY (do-it-yourself) attitude into field biology appeared to be only one of several design tenets at work for the first round of digital naturalists (“Dinasaurs”). Other key themes seemed to include speculative design (exploring possible futures through new arrangements of objects and people), technology for art’s sake (pure play with machines), and multispecies becoming (reframing the category of the “human” through new modes of interaction with nonhuman living beings).

With these themes in mind, I planned to write an ethnographic article about the digital naturalists among whom I would work and live for two weeks. And indeed, in order to learn more about what performing digital naturalism (or not) felt like to the various 2019 conference participants, I conducted a series of sixteen semi-structured interviews, most one hour in length and all richly rewarding. (See below for the interview protocol.) Moreover, I participated alongside many more Dinasaurs as they designed, reimagined, and executed projects or simply explored the tropical moist forest. In a sense, I sought to understand the “typical” experience of a digital naturalist while probing for insights into what digital naturalism means.

Dinacon itself, however, is an anti-disciplinary event where participants are encouraged to eschew formalities and traditions, remix ideas, and remain open to change. In fact, more than the call to bring computer engineering and 3D printing into the forest, the organizers of Dinacon nudge participants to not do whatever they would typically do; to not assume that they are immune to environmental influences, human or nonhuman. This ethos was physicalized by the daily “housecleaning” exercise in which Andy would literally chase participants out of his home/lab, forcing them to pause their work and do anything else for at least an hour (but, in practice, two or three, due to dinner).

So my project to write a well-organized and disciplinarily legible ethnographic article mutated. My article (which, to be frank, is competing as of fall 2019 for attention with my overdue dissertation) remains half-finished. Pages and pages of field notes—thumbed out late at night a while lying on the bottom of a bunk bed—remain half-transformed into coherent vignettes and arguments. On the ground, I allowed my disciplinary practice to be hacked, and my project to be intersected by the humans and nonhumans around me. I joined two collaborative projects, one within my existing skillset and one that pushed me to refine my data management skills.

First, I collaborated with designer Sjef van Gaalen to host a short, intensive speculative design workshop on the future of food production, urban planning, and property law called “Speculative Zoöperations.” Drawing from Sjef’s work in the EU on novel cooperative farm–communities (zoöperations) and my work in the northeast US on high-tech indoor agriculture (vertical farms), we challenged five teams to construct maquettes of future farm–cities.

The result was a frenetic collage of futures, all directly and creatively engaged with climate apocalypse, urban dwelling, and how those dimensions of culture intersect with agriculture and food logistics. One city comprised a giant snail; another consisted of enclaves within giant genetically engineered trees in a newly arable (but not too hot) Antarctica; the third consisted of an fortified anarchist garden in New Orleans; the fourth, a dystopian Neo-Toronto, where citizens dwell underground and live off of mycelium; and the fifth, a unique island ecosystem revolving around giant coconuts engineered by escapist capitalists—a site reminiscent of the laser-shark-infested villas of James Bond villains. All told, these science fictional visions explored real trends in late capitalism, summoning them into abstract life in the form of discarded cardboard, masking tape, and orange or blue 3D-printer plastic.

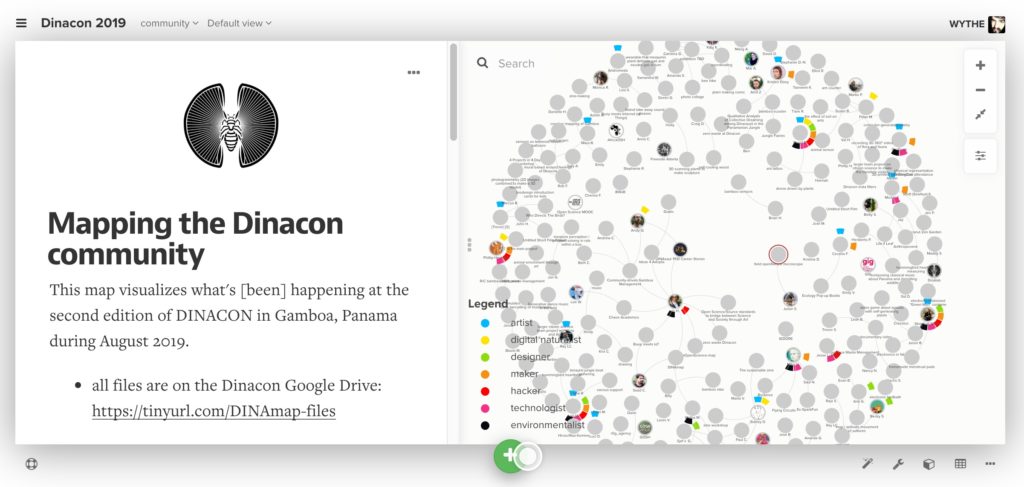

Second, I worked with open science communications specialist Johanna Havemann to collect basic data on all 2019 conference participants and generate a “DINAmap” illustrating their connections to projects, regions, institutional affiliations, and self-identifying tags (drawn in many cases from interviews) such as “maker” or “environmentalist.”

The DINAmap was not meant to be completely exhaustive or richly descriptive, and it’s still open to contributions! It is rather meant to highlight perhaps unexpected shared affiliations and common identities, and to allow us to see at a glance the general diversity (or lack thereof) of participants in Dinacon 2019. All credit to the idea goes to Jo; I simply assisted in data collection and cleaning, and talking through the data visualization hierarchy. This project or a brand-new version moving away from Kumu—which is relatively easy to learn but suffers from the constraints of any free, readymade visualization tool—could continue in future Dinacons. Certainly, the basic demographic information we collected will be interesting to the degree that digital naturalism grows as a discipline and useful to the degree that Andy or other organizers require metrics to show funding organizations regarding the reach of the conference.

Before, during, and long after these collaborative social–visual projects, however, I continued to write field notes and synthesize them into social theories. The following post summarizes my findings, drawing primarily from participant-observation and semi-structured interviews, with both participants and organizers.

Here I do not offer a single cohesive argument or analysis but four reflections that will serve as the basis of an eventual article:

- I discuss at some length how Dinacon functions as an event, including the degree to which Dinacon prompts participants to engage with digital naturalism as articulated by Andy. Then I discuss more briefly:

- the various ways in which Dinacon serves as an exemplar for proponents of a STEAM (science, technology, engineering, art, and math) education paradigm that is more nimble and equitable than that afforded by the Academy;

- the strong aspect of play operant at Dinacon, which runs counter to the pragmatism of both the larger maker movement (which I understand in one sense as seeking to return the pragmatic power of tool-making to the people) as well as techno-capitalism;

- and finally Dinacon in the context of the politics of the Capitalocene (or Anthropocene, Plantationocene, Manthropocene, Planthroposcene, C[h]thulhucene—take your pick): the questions I’m still writing through include, what are Dinacon’s shortcomings as a space of inclusive sociality? What are the politics of the event?

I offer these fragmentary analytic sketches in part in the spirit of the other partial, mutating projects I observed, and in part because I welcome feedback on them. Far from a removed judgment on a welcoming community, I’d rather offer points of discussion for the community. If you, dear imagined reader, have feedback, please don’t hesitate to email wmarschall [at] fas [dot] harvard [dot] edu or DM me on Twitter at @hollowearths.

❧ ❧ ❧

2/3. Nudging toward innovation: swift trust in the (semi-)wilderness

So what is digital naturalism as such? Most Dinasaurs interviewed responded with some version of Andy’s design philosophy. They endorsed this as positive and interesting, even as many interviewees and participant-interlocutors made clear that they do not think of themselves as digital naturalists. When prompted, however, interviewees reflected on the structural differences between digital naturalism as a set of design principles and Dinacon as an event that creates room for other forms of tool-, knowledge-, and art-making. We discussed the nature of this event, and how their own projects fit in.

In general, interviewees and participant-interlocutors felt that digital naturalism was inspiring and could continue to grow as a named, specific technology design paradigm, apart from the event of Dinacon. At the same time, they recognized that Dinacon’s evolution would not necessarily be tightly linked to digital naturalism, but rather to the development of a community or network of individuals with other shared commitments. (I generally gloss these as the principles of maker culture, but there are other ways to think about what brings digital naturalists together.)

Regarding the intersection of digital naturalism as design philosophy and event, most interviewees and participant-interlocutors identified Andy himself as the necessary link: one could summarize Dinacon as a charismatic technological design philosophy being explored in an unconference—or some version of that phrase.

I think we’re all naturally scientists, right? But I think… it helps to have a guiding like a North Star, you know, somebody asking these questions.

—a Dinasaur, contemplating Andy’s role as ur-digital naturalist

Regarding Dinacon as a pure event—a form of socialization, a mode of association, a time- and place-bound coming-together, more than an abstract design philosophy or concomitant (anti-disciplinary) pedagogical model—many interviewees and participant-interlocutors compared it to other genres that bring together dedicated amateurs or professionals from different fields for temporary, project-based creative work: hackathons, summer camps, even transformational festivals such as South-By-Southwest or Burning Man. (At least one participant found the companions to Burning Man pejorative.) I glossed this understanding of Dinacon as event in terms of a professional conference or “unconference,” meaning a conference with a clear theme but little or not set agenda, for makers.

For me, it felt more like a hackathon, but like in the wild and you had to, you know, kind of—you had to get the things that you needed.

—a Dinasaur, on the form of the-event-that-Dinacon-is

Overall, many participants stressed that while Dinacon is more of a general maker conference (an event) than a performance or exploration of a specific design philosophy, Dinacon is not truly a conference at all in the sense of an event with a clear purpose for professionals of one type. One interviewee noted: “Calling [Dinacon] a ‘conference’ is itself a hack,” as in a creative exploitation of a rule. I glossed this not-really-ness as an important element of plasticity (wiggle room or “squishiness”) for a developing event and the developing (anti-/trans-)discipline that inspired it.

Likewise, many interviewees and participant-interlocutors felt that Dinacon was, all at once, thematically about digital naturalism, a more general maker paradigm, and various other, variously allied or counterposed themes. So in addition to the nascent discourse on digital naturalism pur sang, we also discussed other relevant technology, design, science, and art discourses in some depth.

The word that seemed to resonance with the most participants by far was “maker.” A distant second was “hacker,” as in computer engineer interested in software and hardware as platforms for creative play—not, many were quick to point out, as in virtuosic computing amateur interested in stealing online identities or state secrets. “Tinker” also came up as a relevant category, implying a maker who works incrementally.

…Hacking is not necessarily, you know, stealing credit cards and doing notorious things… It is really about taking things and using them for unintended purposes or re-purposing other things for new things.

—a Dinasaur, thinking through making, hacking, and tinkering

Other relevant discourses included open science and technology (the conference budget, for example, is open), technology art (making a spotlight-drone controlled by a plant’s electrical signals for humans to dance under, e.g.), molecular biology (genetic barcoding of wild yeast strains, e.g.), and field biology—that is, naturalism avant the digital (various projects to draw, digitally image, record the sounds of, or otherwise simply describe “nature”).

Of course, some projects did fall neatly within Andy’s original concept of digital naturalism as bringing the tools of computer engineering and makerspaces into sites of field biology research: Andy himself, with help from several others, continued to work on automated ant-counting to help entomologist Peter Marting, a collaborative project that was one of the original inspirations for digital naturalism. Many projects, in fact, focused on making new tools, especially sensors.

The project to create yeast traps, isolate wild yeast strains, and barcode their genomes also clearly adhered to the tenets of digital naturalism as a design philosophy for technologists interested in field biology: the project creator even told me, “I want to do fieldwork. … I want to understand microbial diversity in the wild.”

Beyond some clear structural elements that made Dinacon a coherent event, and beyond thematic groups of projects, a final thread clearly ran through the collaborative projects that I observed: this could be called “swift trust,” or the coming-together of professionals with different expertise to work on common goals over a relatively short period of time (coined by first Debra Meyerson in 1996). As in the movie industry, and contra the timescales of most scientific research, Dinacon projects had to be started, refined, and completed within one or two weeks, sometimes less. Often, they began as solo or small-group projects but added elements that required or enabled new collaborators to join.

This process of rapidly gathering new perspectives included formal feedback sessions and informal articulations (“what are you up to?”) over hikes and meals. Ideally, projects’ stakeholders felt that they entered what Andy called a “flow state,” picking up useful elements from the context of Gamboa and from other Dinasaurs.

Everybody has their contribution, right? So you’re instantly aware of the parochialism of your field, like the narrowness of your training once you meet all these other people.

—a Dinasaur, asked about collaboration

…You’re working with an unknown parts list until everyone arrives.

—another Dinasaur, contemplating project design

Ultimately, all curveballs, resource constraints, and new ideas, good or bad, had to fit within a limited number of days to execute a project. Some projects consisted of performances and could be ultimately finished, but some were left half-finished, open-ended, or as first parts or instigations. Dinacon’s organizers did not of course fully impose a swift trust-driven production flow onto project creators a là the Hollywood movie industry. Instead, the clear goal of accomplishing some sort of project and soliciting some sort of feedback within a certain time frame, with the design philosophy of digital naturalism in the background, offered participants guidelines or nudges, gently contouring their social and technical experience toward collaborative, biology-focused projects with one- or two-week scopes of work.

In summary, Dinacon is at least two things at present: a design technology for technologists interested in working with life scientists as well as an annual gathering in a tropical forest of self-described hackers, makers, scientists, artists, and other creative individuals.

Somehow, Dinacon as a total intellectual, emotional, and physical space manages to be both meditative and intense, rule-free and anxiety-provoking. This strikes me as rather the point: if it were merely a meeting of open hardware engineers or only ornithologists or only kinetic sculptors; if less booze were involved; if less internalized pressure to produce work were felt;—if any of these counterfactuals were true, Dinacon would lose its charm as a site where generations meet, disciplinary norms are transgressed, myriad projects unfold and half-unfold and crash, and—most importantly—these tensions must be actively discussed, because you’ll see the same people at dinner and breakfast for a week; because you want to write songs with them and go on long hikes with them; because you’re working on a sensor project together; because you are all out of your element and collectively exploring.

❧ ❧ ❧

3/3. Beyond toolmaking, beyond hacking: other ways of reading Dinacon

The above reflection focuses on Dinacon as a space—a time frame, a physical locus—within which technical work of some kind was accomplished. The following shorter reflections focus on kinds of work Dinasaurs they performed, beyond that encompassed in the definition of digital naturalism.

Reimagining the future of STEAM: digital naturalism as educational paradigm

To some degree, many projects did not seem to have a pragmatic objective in mind: the tools they created were non-functional, or the data they collected (length of stay in Gamboa mapped out in a histogram made out of leaves, e.g.), hard to draw meaningful patterns from. The purpose of these projects seemed to be instead to refine one’s skills, to learn about the town of Gamboa and especially the tropical forest surrounding it, or to teach others something. Thus many projects or non-project creative activities at Dinacon seemed to be educational in nature. Skill-sharing workshops were especially common. Most participants seemed eager to share knowledge, with no sense of pedantry. One interviewee reported that the biggest problem with Dinacon is an inevitable feeling of “FOMO” (fear of missing out) vis-à-vis all of the activities offered.

My personal favorite workshops were one on training machines to write poetry using a web app and some sample texts, including a delightfully dry passage about agoutis, and one on forest bees.

Owls for the Kingdom (Cento)

—poem composed from lines generated by a computer

She is seeing owl worlds. Then

actual owls, which explains the

rush of time left over. But the

owls are born in name alone—

cut from inside-out colonies

on a world planted in the

forests. Here, not order—contrast.

But these projects and teaching moments might be best understood as metonyms: Dinacon as a whole can be seen as an earnest, well-designed attempt to model a new détente between the Academy, capital A, and some form of making/doing-focused “unschooling” that feels decidedly non-capital-A-Academic. That is, perhaps more than allowing individual makers or small groups of them to explore interesting projects in semi-wild areas, Dinacon’s primary offering is modeling a way to organize learning by making. This is not an entirely novel idea. Andy stressed when interviewed that he teaches computing and hardware skills by bringing students outside, so in a way, digital naturalism is already at work as a practical mode of tech education, and perhaps as a fully theorized philosophy of pedagogy. But Dinacon offers a showcase space, a transformational event for makers and educators to explore new ways of teaching.

Perhaps some of the makers who come to Dinacon will be inspired and take away ideas about how to educate in their areas. Digital naturalism could very well grow into a common approach for teaching various subjects, particularly those under the STEAM umbrella: Dinacon seems to promote exploring new technical subjects and skills in small groups, in relaxed settings, with few or no concrete outcomes set in advance. One can imagine even more community-wide projects at future Dinacons, to be explored as jigsaws; this idea appealed to several interviewees, who related it to citizen science but differentiated digital naturalism as more about tech skills than epistemic questions per se. One interviewee suggested that future Dinasaurs plant some to-be-determined number of trees appropriate to a visited region. I suggested that we work with local primary and secondary schools, or that we first ask local indigenous peoples what environmental issues they would most be interested in visiting technologists researching.

In any event, for educators, Dinacon offers a chance to rethink what teaching looks like, since a house/makerspace in a ghost town in the tropical forest is not a traditional classroom, and one’s fellow Dinasaurs, not traditional learners.

So yeah, I would like to share something before I leave, yeah. I never leave one place without showing or sharing something about bees.

—a Dinasaur, two days before leaving Gamboa

Escaping the tyranny of pragmatism in maker discourse: a celebration of useless endeavors

At the same time that Dinacon is practical qua project-focused and educational qua post-Academic skill-sharing-focused, it is also a space of pure jeu or play: many projects featured elements that serve no purpose whatsoever, and many days featured moments that were never meant to serve any particular project. Play can be thought of as a rehearsal of creative moves with no goal in mind, as opposed to “mere” fun (a diversion, pure entertainment).

Both dimensions of activity were present at Dinacon, but the philosophy of the event seemed to push participants toward play. I recall many times a fellow Dinasaur stressing that her real “project” was simply to walk through the forest and look for animals. (For me, it was plants.) Andy said that much of the point is simply to encourage the act of “crafting in nature” without stressing specific outcomes.

I personally experienced play at Dinacon in two modes: the first was an invitation to try new things, loosen or change old ones, and especially to explore Gamboa and the forest. This led, for example, to my collaboration with Sjef on Speculative Zoöperations, which was an ultra-fast, compressed version of two different day-long designs workshops with slightly different goals and background lectures. The result was not pure play, in that we still had some pedagogical goals in mind and gave our good-natured participants several specific tasks to complete (create a maquette, name a future city, explain the food system there, respond to a climate catastrophe, incorporate a new cohort of person/market, etc.). But the feeling of playing around with ideas of what future-oriented ecological design is, and how to explore that practice with others, pushed the workshop into existence in the first place.

An example of a second, more pure mode of play was what I called in my field notes “drone fever”: during the evolution of the plant-driven drone-with-a-giant-spotlight-on-it project, the overgrown baseball diamond—the hollow center of the empty colonial town—would be periodically flooded with light for what felt like a quarter of an hour (I don’t know if anyone in the bleachers kept time) as the inchoate frankendrone danced. Bugs fogged the pillar of light as humans oohed and aahed.

I’m sure these flights served some testing purpose for the dronemaker, but for the rest of us, they served as a coordinating ritual akin to a religious sermon. We sat and took pictures and wondered about the future together: how ubiquitous will delivery drones become? Drones in science? Security drones, which of course promote the insecurity that neo-nationalist austerity states thrive upon? Pet drones? Watching someone play around with both technology and a plant in the dark felt rewarding not because we learned anything specific, but because we collectively attended to what felt like an intrusion from the sometimes inspiring, sometimes techno-dystopian future into a quiet idyll of the present. We experienced non-pragmatic making that also didn’t feel like art—a test run, not in a gallery, hardly announced, unclear start and stop times, repeated often.

Likewise, when one Dinasaur discovered that it is both medically safe (short-term) and culturally appropriate to smoke warūmo—the leaf of the ubiquitous, elegantly skinny cecropia tree—at least a few if not many of us played around with this new, free, mild substance. Its smoke was supposed to function like CBD but only ever seemed to function like tobacco. I never learned the full story about how it is traditionally prepared. Maybe no one particularly enjoyed it. The point certainly wasn’t really to learn about plant physiology by smoking it. Instead, the discover of warūmo concretized for me human relationships, not to mention my relationship with the important cecropia tree. Smoking was play that made people and trees more memorable.

In the same way, I barely improved my soldering skills at Dinacon, never did learn to weld, and only wrote a few lines of code for simple web apps—but the event made me remember how those skills work, why they matter, how I might explore them in the future. So in a sense pure play did serve a function by helping a community to form and educational activities to appear approachable.

Pure play might be a pole at one end of a spectrum, the other being pragmatic activity designed to result in some documentable progress or achievement. Rather than simply standing apart, completely separated, however, these poles are always pulling upon each other. It is as hard to imagine Dinacon without play as it is to imagine it without the sharing of practical skills.

Debating the vocation of the maker in the age of climate apocalypse: against an apolitical digital naturalism

Finally, I must discuss another way in which Dinacon functions, and another thing that it is, or may be, or will be, depending on who organizes and attends and writes about it over the next several years. For Dinacon is a boundary object, an entity that stakeholders have some investment in even as they don’t agree on what exactly it is. And Dinacon may change very much in the near future—even if all stakeholders are happy with its current format—in response to climatic and attendant political disruptions of all kinds.

So regarding this boundary objet, I have so many questions. What are the politics of Dinacon, folk (meaning unofficial, ad hoc) or otherwise? Is Dinacon a redoubt, a vacation, a training camp, a place temporarily removed from larger social struggles? How to reconcile the experience of driving through an economically blighted barrio in Cuidad de Panamá with the opulence of the gleaming new postmodern edifice home to the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI)?

Does the emergent culture of Dinacon sufficiently depart from a larger maker culture, one that is typically white, male, and above all neoliberal? Can future Dinacons better nudge makers to think about and perhaps abnegate or share their own privileges? Can future Dinacons better plug into local communities, addressing local environmental challenges? Can Dinacon more explicitly offer a response to climate apocalypse?

Widening out, what function should a traditional education in technology play, if any, in an imagined ecotopia? What role should makers and hackers play? What is the capital-P Point, the telos (to be fancy), of the maker in the age of climate apocalypse and neo-nationalism? And how does Dinacon fit in?

At least a few participants struggled with these lines of thinking, and arguments about them at times arose that, however friendly, revealed, real disagreements about the roles of Dinacon-the-event, digital naturalism-the-design-philosophy, and technology overall in various possible futures. These fissures led me to believe that, regardless of the answer to the questions posed, Dinacon functions as an important crucible for asking them.

Since Dinacon is not only a boundary object but an event wherein clever people exploit rules and adapt to new circumstances, I predict that its role as crucible for nudging makers to debate serious questions about the connected, living fragile world will become more important as the event grows and circumstances indeed change. Future projects will no doubt hack Dinacon in order to manifest (eco-)political changes. The anti-politics of technology—pure efficiency, by twentieth-century industrial standards—will fade in relevance. I look forward to learning what emerges in their stead.

❧ ❧ ❧

Appendix: interview protocol

Here is the list of questions I asked during hour-long interviews. In many cases, due to the flow of a given conversation, I swapped the order of questions or reworded them in minor ways.

Re feedback, I solicited it during and especially after interviews, depending on time. I owe a sincere thanks to all of the interviewees who shared their thoughts on specific questions and my overall line of inquiry. This version incorporates many changes based on this feedback.

❧ Hello. I’m an anthropologist of ecological technology and design. My research examines communities that come together to imagine and then instantiate new futures for living environments. Dinacon provides an excellent case for the study of such a community. I plan to research and write an ethnographic article about how digital naturalists form a community, building “swift trust,” and then work together to accomplish various goals. May I ask you a few questions about your participation in digital naturalism and Dinacon?

❧ May I record this interview? Thanks!

❧ Would you like you me to keep your answers anonymous, or do I have your permission to write about your work by name?

❧ Can you please state your name and title, and then briefly describe your project at Digital Naturalism 2019?

❧ How did you hear about Digital Naturalism?

❧ Why did you ultimately decide to attend?

❧ Did you have institutional support to attend?

❧ Can you tell me a bit more about your project? How has it evolved since you’ve arrived in Gamboa?

❧ How motivated are you to finish the project you initially pitched? To finish on time?

❧ Have you looked at the book detailing Dinacon 2018? Are you at all motivated by that sort of documentary artifact?

❧ Are you working with other Digital Naturalists at this event? Talk to me about collaboration. In general, and at Dinacon.

❧ Do you speak Spanish?

❧ What do you think of Gamboa? Is this site of particular interest to you? Would you be as likely to attend a future Dinacon elsewhere?

❧ Have you been hiking or swimming yet? Where? How has that affected your project, if at all?

❧ What counts as sustainability for you?

❧ In your opinion, what aspects of a living environment should be conserved? What role does technology play in conservation or preservation of living environments? Any good examples spring to mind?

❧ What makes a technology, or an application of one, instrumentally or morally good?

❧ What is hacking?

❧ What does the phrase “digital naturalism” mean for you?

❧ Do you think of digital naturalism more as a design philosophy for technology (set of guidelines for making tools), a discipline (academic category, teachable), a movement (social grouping, event- and leader-focused), or an imaginary (vision for society)?

❧ What kind of event is this? Burning Man or summer camp? Hackathon or academic unconference? Or detox? Or cult?

❧ What values characterize digital naturalism as novel?

❧ Do you think that events such as this Digital Naturalism conference will help transform traditional disciplines or institutions? If so, how so?

❧ What role does digital naturalism play in global movements for planetary health and environmental or social justice, or climate change mitigation? Policy?

❧ Who else should be included? What about people not from intellectual, “creative” backgrounds?

❧ Is maker culture inclusive, overall? How can it be moreso?

❧ Should Digital Naturalism seek more institutional support, e.g. from a university? What about prize money?

❧ What are you reading? What inspires you?

❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧